You are here

New Insights on Forests in a Changing Climate

How will climate change affect New England forests over the next century? According to a series of new studies from HF Senior Ecologist Jonathan Thompson's lab, the answer is a mixed bag. In some respects, climate will exert an even greater impact than we thought: longer growing seasons will mean more tree growth and carbon storage. In other ways, climate impacts are likely to take a backseat to other factors, like the forests' continued recovery from colonial-era deforestation.

The three new papers employ a robust new landscape simulation model developed by Thompson's team with support from the National Science Foundation's Long-Term Ecological Research Program. The models were validated with decades of data from atmospheric towers and study plots at Harvard Forest and other sites around New England.

The first study, by Yu Liang, Thompson, and others in Global Change Biology, modeled how trees' home ranges may shift in the future, with climate change as a constant, but not sole, factor. The team modeled additional real-world forest dynamics like interspecies competition, dispersal of new seedlings, and a range of tree-removing disturbances, like timber harvest. The study confirms that tree species turnover is an inherently slow process - one that cannot be dictated solely by temperature. So, while tree species' preferred climates are moving rapidly northward, the physical migration of trees remains comparatively slow. The factors paving the way for range shifts for species at the leading (northward) edge of the region - basswood, birch, cherry, oak, and pitch pine - are likely to be the species' photosynthetic capacity and their ability to compete for light. Ability to disperse seeds was an added predictive factor for trees at the trailing (southward) edge of New England - spruce, poplar, fir, ash. The study underscores the importance of understanding how interspecific competition and disturbance - and not solely climate - affect trees' ability to shift north.

A paper in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences, by Matthew Duveneck and Thompson, modeled the next 90 years of tree growth in New England, taking into account the seasonal dynamics of climate change. Despite warmer summers slowing tree growth in July and August, longer springs and autumns will result in an overall rise in annual growth and carbon storage, helping to counter future climate change.

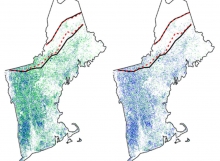

A third paper, in Landscape Ecology, modeled the next 100 years of forest species composition and growth dynamics, with and without climate change scenarios as added factors. Every scenario of climate change led to increases in biomass (tree growth), especially in the younger, more disturbed forests in the eastern part of New England. Even with climate as a factor, the continued recovery from colonial-era deforestation remained the dominant driver of species change and growth dynamics, implying that New England's forests have a lot more growing left to do.

Future work by Thompson's team will build off of these findings as part of the larger New England Landscape Futures Project and the S3 RCN, also funded by the National Science Foundation. A forthcoming suite of studies will overlay these climate scenarios with alternative land-use change scenarios to create a fuller picture of the interplay between human decision-making and the natural environment over time.

- Read the full scientific papers:

- Global Change Biology: How disturbance, competition, and dispersal interact to prevent tree range boundaries from keeping pace with climate change

- Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences: Climate change imposes phenological trade-offs on forest net primary productivity

- Landscape Ecology: Recovery dynamics and climate change effects to future New England forests

- Learn more about the research in Jonathan Thompson's lab.