With a 4,000-acre campus located on ancestral Nipmuc land, the Harvard Forest is committed to working in meaningful relationship with local Indigenous communities to guide our research, conservation approaches, and educational programming. The list below is not an exhaustive accounting of our relationships (relationships can never be fully described in a website!). Please reach out if you have questions or would like to engage! HFoutreach@fas.harvard.edu

Student Experiences

We are grateful to the Nipmuc community for their thoughtful engagement with our growing community of student interns. Primarily through winter and summer internships, we co-develop research to foster a more collaborative and just understanding and practice of science and conservation.

To Be Seen: Acknowledging Indigenous Land in Green Spaces

In early 2023, Harvard University student interns Tyler White and Kashish Bastola worked with Nipmuc community leaders to reexamine interpretive signage on Harvard Forest’s trails to be more inclusive of Native American ways of knowing. Supported by Harvard University’s Culture Lab Innovation Fund grant, this project was led by Harvard Forest postdoc S. Joseph Tumber-Dávila. New trail signs along the Manchage Manexit trail acknowledge the vitality of Nipmuc stewardship of the land and ask the viewer to interrogate their own role in recognizing and amplifying the Nipmuc voice in future land stewardship decision-making in the region. Learn more about the trail here.

Centering Indigenous Knowledge Around Invasive Species Management

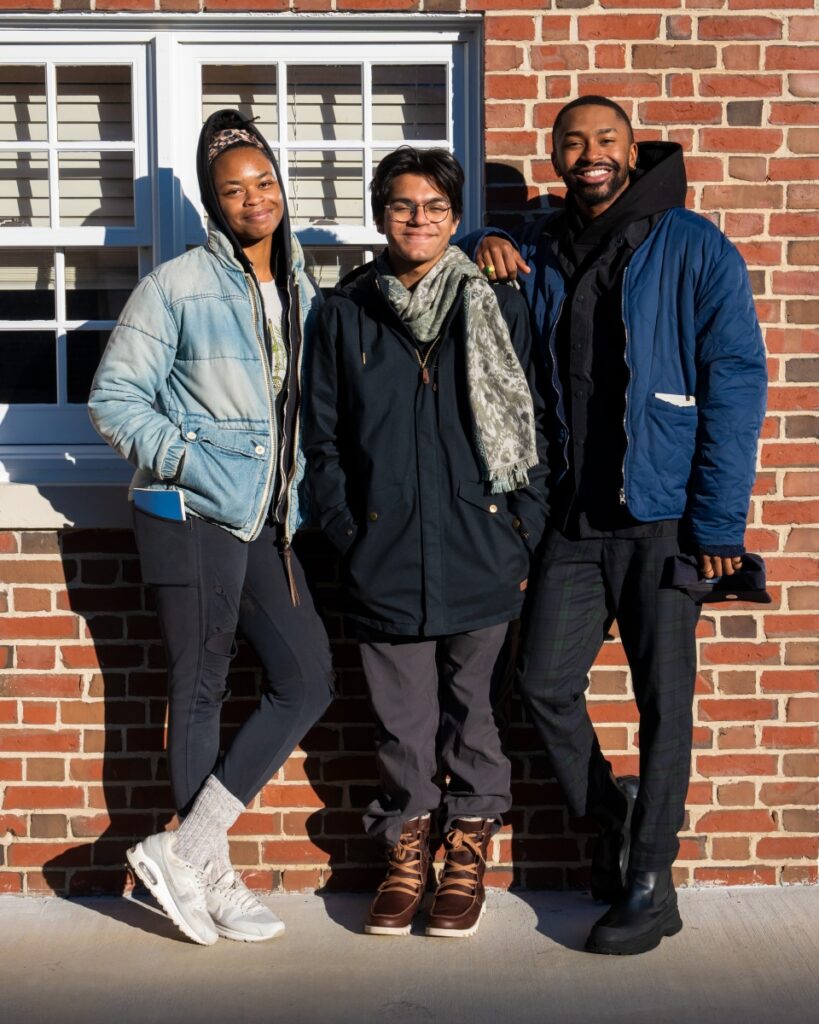

During the summer of 2022, student interns Santiago Alvarado (Rhode Island School of Design) and Rachel Carethers (Wellesley College) worked with Nipmuc community leaders and Harvard Forest researchers Meg Graham MacLean and Danielle Ignace to examine the relationship between non-native plants and those of significance to the Nipmuc community. With a strong emphasis on listening and learning, the interns created a pilot study to examine community relationships between two native plants and the “invasive” multiflora rose. As Rachel states, “We explore what it means to be in kinship with a contrived category of non-native plants – presently known as ‘invasive’ in the western science framework – in relation to plants significant to Nipmuc people.”

Fisher Museum

Since 1941, the Fisher Museum dioramas have depicted landscape change in central New England beginning with European colonization in 1700. While these internationally-acclaimed models provide valuable insight into factors controlling the patterns and dynamics of the post-colonial landscape, the absence of Native Americans in these schemas is an inexcusable symbol of erasure.

In 2021, a panorama honoring Nipmuc stewardship and collaboration was installed in culmination of a year-long collaboration between Nipmuc community organizer Nia Holley, and multimedia artist Roberto Mighty. The photograph, spanning a 24-foot wall in the museum, depicts the east branch of the Swift River, in an area that has been known for millennia as Nichewaug.

Our collective hope is that this project continues to further necessary conversations about the past, present, and future land stewardship by the Nipmuc people – a conversation which continues to inform and transform discussions and actions on research, education, and land management at Harvard Forest.

Research

Harvard Forest Senior Ecologists Jonathan Thompson, Dave Orwig, and Neil Pederson each work in relationship with Indigenous communities in their research, collaboratively building research questions and programming – particularly with the Nipmuc here in Massachusetts, the Penobscot in Maine, and a growing number of tribes outside the Northeast.

Examining Land Conservation Tools

As our relationship with the Nipmuc and other tribal communities grows, so too does our understanding of the issues surrounding modern-day and state-promoted land conservation tools. Through conversations with Harvard University’s Emmett Environmental Law and Policy Clinic, Nipmuc community members, and land trust practitioners in the region, we are committed to incorporating tribal voices into our understanding of how land conservation might move away from the traditional conservation easement tool to incorporate more equitable ways of ensuring land is honored and stewarded for generations to come.