You are here

Bullard Spotlight: Nipmuc Rematriation with Sonksq Cheryll Toney Holley

With a 4,000-acre campus located on ancestral Nipmuc land1, Harvard Forest was humbled to receive a Bullard Fellowship application from Cheryll Toney Holley, the sonksq (female leader) of the Hassanamisco Nipmuc Band2. A respected historian, genealogist, and author, Toney Holley co-founded the Nipmuc Indian Development Corporation to assist in the revitalization of the Nipmuc community.

Central to the wellness of the Nipmuc community – including the land – are kinship-based relationships that strengthen connections with ancestral lands and allow the restoration of sacred traditions. Through this process of rematriation, the Nipmuc community is actively reclaiming traditions and values, including food sovereignty, ceremony practice, and land stewardship. The return of land to the Nipmuc, or landback, has begun occurring and allows the rematriation of cultural practices that are integral to healing.

Central to the wellness of the Nipmuc community – including the land – are kinship-based relationships that strengthen connections with ancestral lands and allow the restoration of sacred traditions. Through this process of rematriation, the Nipmuc community is actively reclaiming traditions and values, including food sovereignty, ceremony practice, and land stewardship. The return of land to the Nipmuc, or landback, has begun occurring and allows the rematriation of cultural practices that are integral to healing.

Beginning with the Farm School returning 188 acres of farmland to the Hassanamisco in 2023, several other entities are in discussion with the Nipmuc community about potential landback projects. Inquiries to support rematriation have recently increased, which has led Cheryll Toney Holley to focus on aligning the community’s values and traditions to create a tribally centered approach to stewarding the land.

During her 2023-2024 Bullard Fellowship, Toney Holley has been working from an all-of-community model (typically used for language reclamation) to concentrate on identifying two aspects of community growth each season. In poponae, winter, the group focused on art & economic development; in sequan, spring, the group is focusing on agriculture & job training; in neppinae, or summer, the group will focus on conservation & public safetly; and in ninauwaet, or fall, the group will focus on education and health.

With inspiration from Eve Tuck’s Rematriating Curriculum Studies, Toney Holley’s work incorporates community surveys, focus groups, visits to the land, storytelling, and newsletters. Recruiting community members from all generations, the project fosters collaboration between family members & elders, cultural leaders, language instructors, public relations leaders, and food sovereignty and health service workers.

“Our intention is to create a plan that is influenced by our traditions, sovereignty, language, community, environment, knowledge, and the land itself,” shares Toney Holley, “We believe that recognizing and building on the connections between the people, land, water, and our more-than-human kin requires intergenerational support and involvement at every level.”

“Our intention is to create a plan that is influenced by our traditions, sovereignty, language, community, environment, knowledge, and the land itself,” shares Toney Holley, “We believe that recognizing and building on the connections between the people, land, water, and our more-than-human kin requires intergenerational support and involvement at every level.”

Above images courtesy of Cheryll Toney Holley

1. Thumbnail image shows bloodroot in bloom.

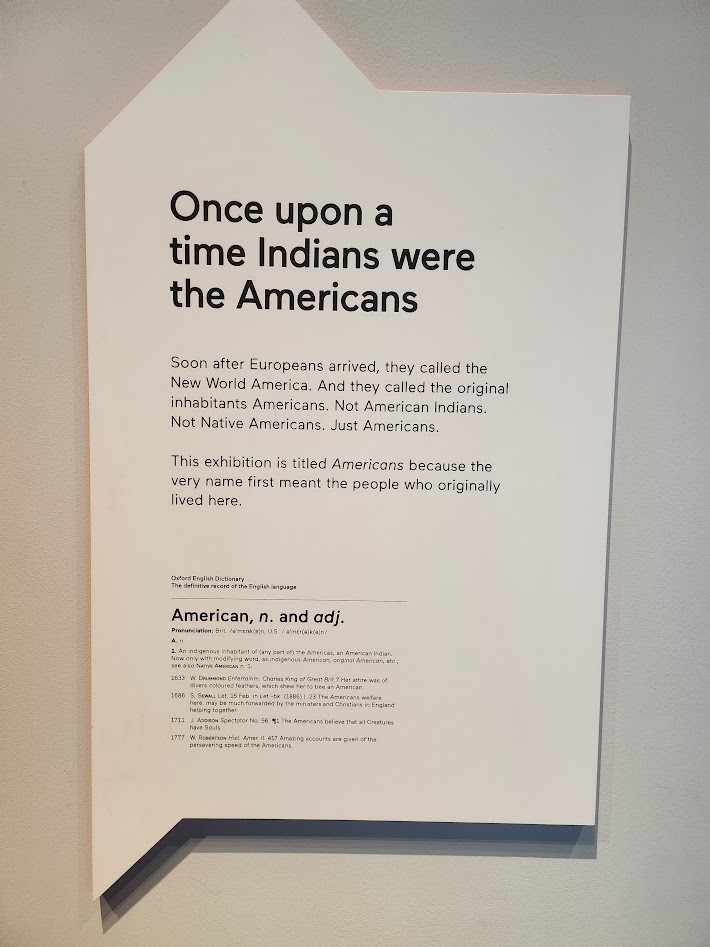

2. Photo shows a plaque from the Americans Exhibit at the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian.

3. Photo shows sweetgrass in bloom.

4. Photo shows herring, a culturally significant species, in a bucket.

------------------------------

1The homelands of the Nipmuc, meaning “freshwater people,” extend throughout central/western Massachusetts and include portions of Connecticut and Rhode Island. Following the tragic genocide and forced removal/assimilation of Indigenous people in the region, Nichewaug was colonized by European settlers and incorporated as the town of Petersham in the 18th century. The original 2,000 acres that make up the Harvard Forest were donated to Harvard University by James Brooks.

2The Hassanamisco are one of several Nipmuc bands. Despite colonial coercion, brutality, and centuries of systemic settler-colonial policies aimed at reducing Indigenous sovereignty, the Hassanamisco Nipmuc band has retained stewardship of their 3.5-acre Hassanamesit reservation in Grafton.

By Emily E. Johnson