A new study in the journal People and Nature, led by a team of scientists from Harvard Forest, UMass, and Duke University, surveyed hundreds of forest landowners in New England and found that future invasive insect outbreaks could increase the likelihood of forest harvest on private land.

Based on survey responses, the team grouped landowners into three types, characterizing their potential reactions to a future invasive insect outbreak:

- The largest group, 46% of respondents, expressed that they would cut in the event of an insect outbreak, regardless of its severity.

- For the next-largest group, 42% of respondents, intentions to harvest trees were influenced by the severity and duration of the insect outbreak.

- The smallest group, 12% of respondents, expressed low intentions to harvest regardless of the type of outbreak.

This likelihood of harvest – expressed by more than 80% of landowner respondents – is a significant increase over the landowners’ own reported past harvest practices (just over half of respondents reported having harvested before).

Private forest landowners own most of the forest land in New England, and the Northeastern U.S. is dense with invasive insects. The authors suggest that the collective actions of forest landowners coupled with the spread/emergence of forest pests could have significant impact on forest biomass in the region.

This study was funded by two grants from the National Science Foundation.

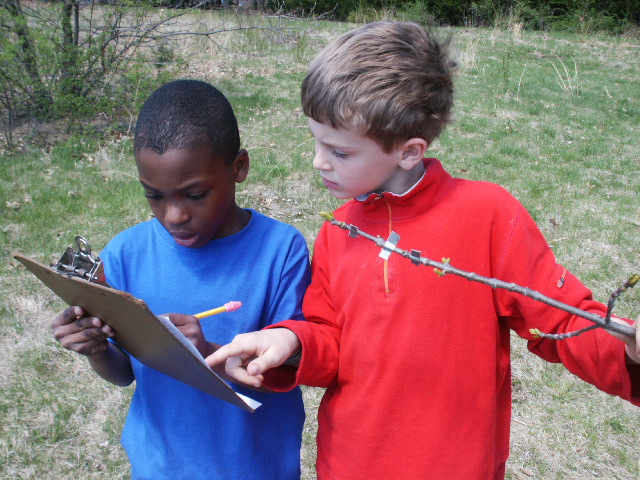

(Photo by Rob Lilieholm)