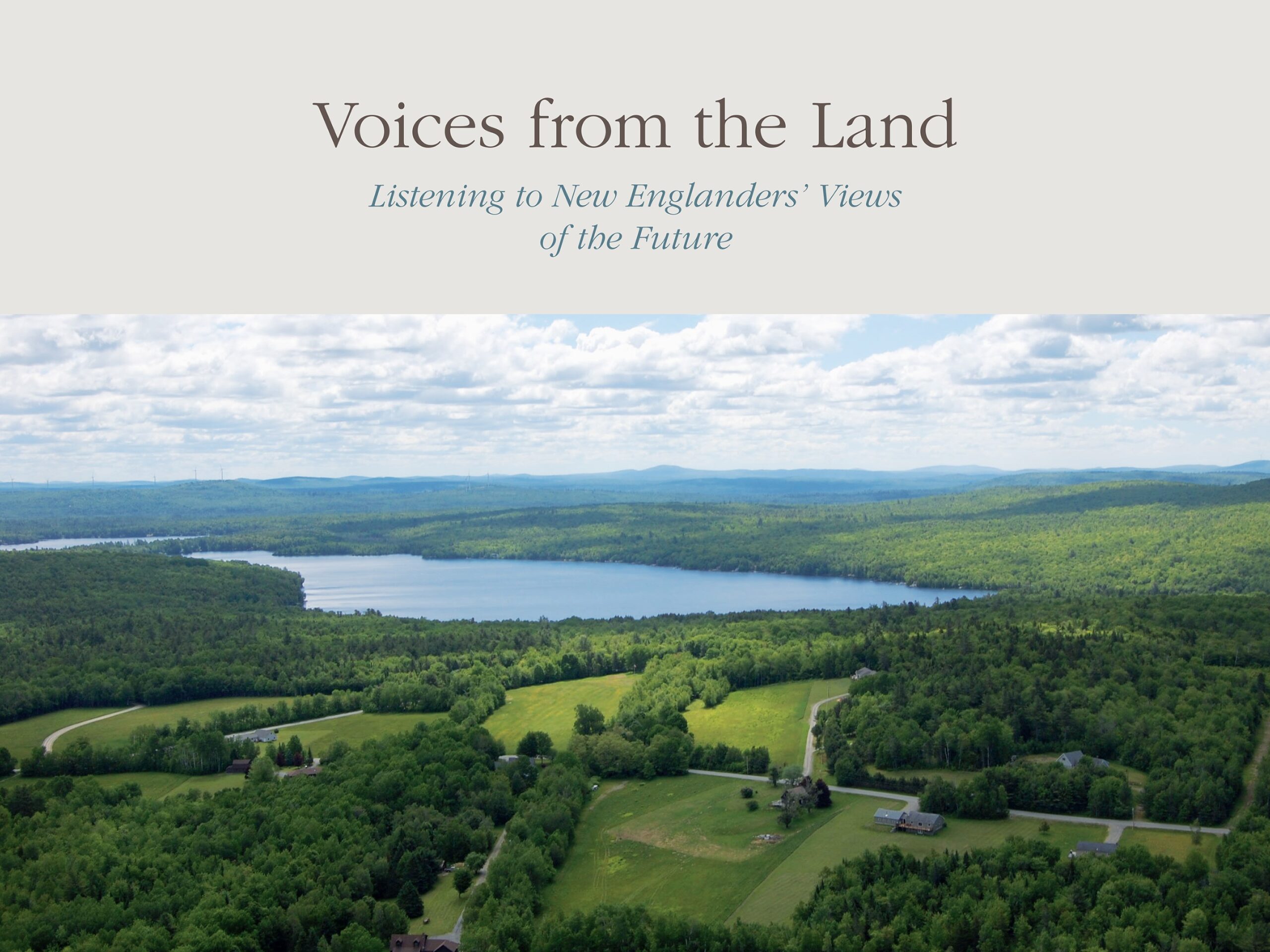

Since 2015, Harvard Forest has hosted a Harvard undergraduate intern for 3 weeks each January, in partnership with the Harvard Office of Career Services’ Museum and Arts Fellowship program.

This year, the Forest hired three interns to work on a range of multimedia projects for the Wildlands and Woodlands initiative, highlighting the role of universities in land conservation across New England, including a conservation story map and a podcast episode.

The interns (Angelica Torres, Julian Rauter, and Amy Li) joined Harvard Divinity School student Alexa Rice, who is completing a Field Education Placement with the Forest this semester, to explore the landscape on field walks (one pictured here) during their three week fellowship.