This spring, 194 K-12 teachers from around the nation enrolled in an online course featuring three Harvard Forest ecologists discussing poems related to their research. The online course is part of the Poetry in America project, created and directed by Harvard professor Elisa New — a public television series and multi-platform digital initiative that brings poetry into classrooms and living rooms around the world.

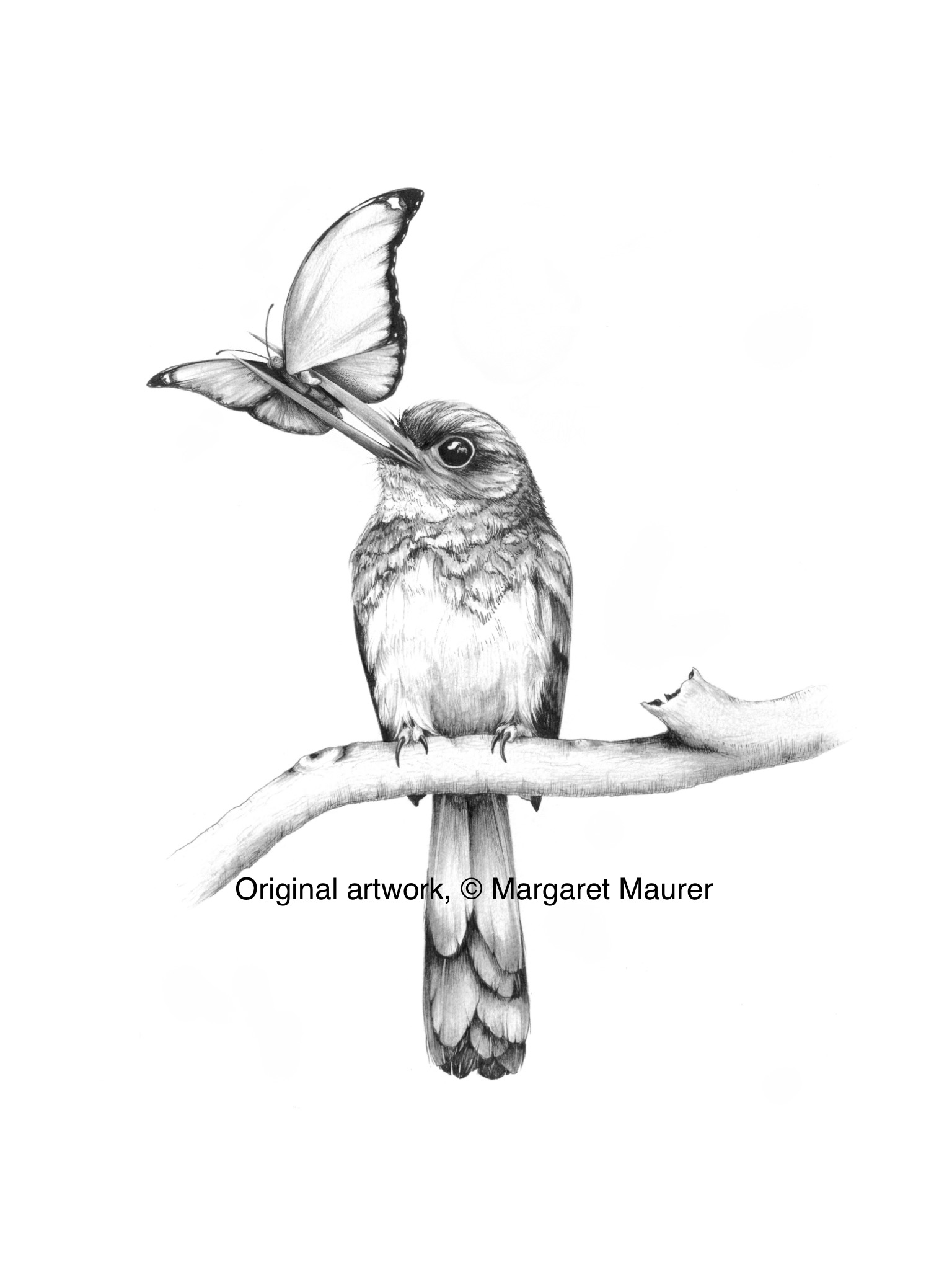

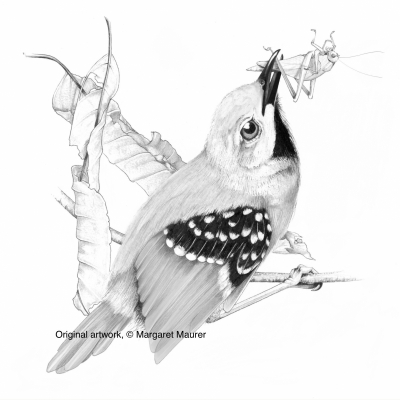

Featured scientists were interviewed in the field, reading poems aloud and connecting specific themes and vocabulary to their own ecological research. Senior Scientist and Site Forester Audrey Barker Plotkin read the poem “The Oak Tree at the Entrance to Blackwater Pond,” by Mary Oliver. Longtime research collaborator Serita Frey, a microbial ecologist at the University of New Hampshire, read “Mushrooms” by Sylvia Plath and “Weakness and Doubt” by Kay Ryan. Noah Charney, a recent Harvard Forest Bullard Fellow, read “The Pond” by Gregory Orr.

The project’s public television series, Poetry in America (presented by WGBH Boston and distributed by American Public Television), has been broadcast nationwide. The project’s for-credit and professional development courses are offered in partnership with Harvard University and enroll undergraduates, graduate students, and educators.

- Learn more about Poetry In America’s online course.

- Learn more about arts & humanities at Harvard Forest.