Old and mature forests are a refuge for the human spirit, homes for rare and fragile species, and crucial allies in cooling our warming planet. Join us on September 24 at 7pm for a discussion with author Lynda Mapes about old and mature forests: why they matter, how we have lost so much of them, and why we must save what remains.

Lynda is an environmental reporter and author whose new book, The Trees Are Speaking: Dispatches from the Salmon Forests, (University of Washington Press, 2025) invites us into a new relationship with and understanding of old and mature forests.

Centered in this story is the connected history of the loss of these forests, beginning in the Northeast with colonization and the arrival of cut and run commodification, continuing across the country and still today supercharging the logging of old growth in British Columbia. Across 500 years and 3,000 miles, The Trees are Speaking bears witness to the displacement of the original knowledge systems and teachings by which these forests and the salmon they nurture, both Atlantic, and Pacific, were cared for and used for thousands of years.

Lynda will also talk about solutions she witnessed underway in local community efforts, and in the Indigenous-led restoration of the Penobscot River, where salmon, river herring and other sea run fish are coming back to the river and even in forest tributaries where they have not been seen in a century, thanks to forest and river restoration projects underway. There is no one solution, but many ways in which communities with an ethic of reciprocity and respect are coming back to the first teachings that stewarded these lands, and getting results.

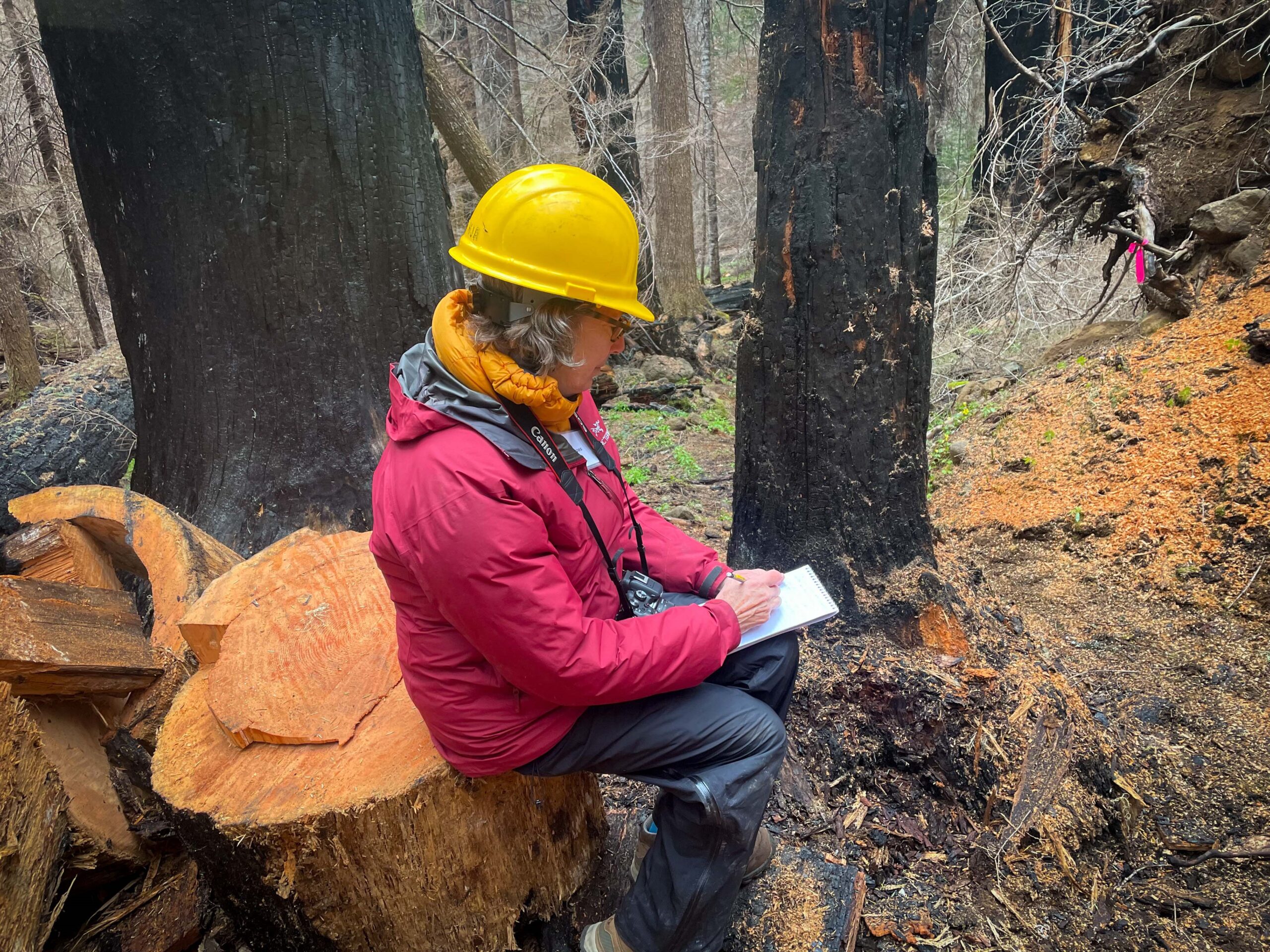

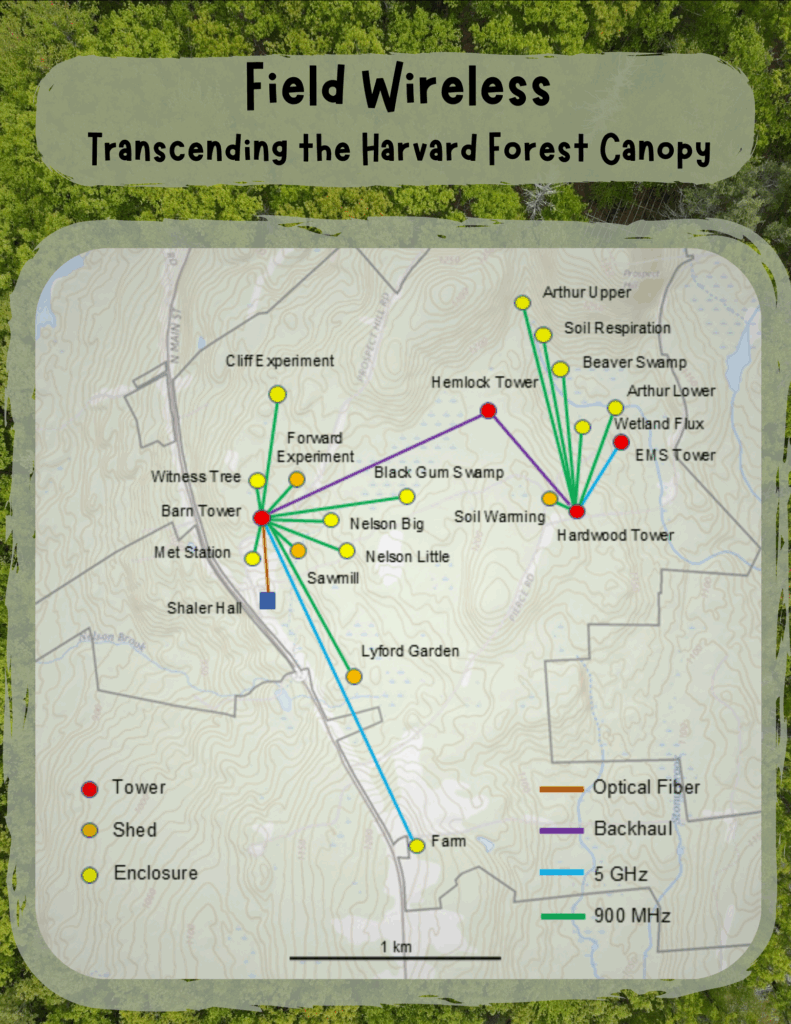

She’ll share selections from her book at the event, and a slide show from her field reporting, with scientists from the Harvard Forest in old growth stands in the Adirondacks; in the forests of Maine with Penobscot Nation forestry professionals and commercial loggers; and with Native culture keepers and scientists in the old growth of British Columbia, Washington, and Oregon.

Lynda reported and wrote this book in part with the support of Harvard Forest scientists, and a Bullard Fellowship in Forest Research while in residence at the Harvard Forest in 2022-23.

This event will occur at Harvard Forest on September 24 at 7pm; learn more here. RSVP not required.

Lynda V. Mapes specializes in coverage of the environment and Indigenous cultures and governments. Over the course of her 27-year career as a reporter at The Seattle Times she earned numerous awards, including twice winning the international 2019 and 2012 Kavli gold award for science journalism from the American Association for the Advancement of Science, the world’s largest professional science association. She and a team of journalists at the Seattle Times were finalists for the 2025 Pulitzer Prize for local reporting.

She has written seven books, including most recently The Trees are Speaking, Dispatches from the Salmon Forests just published by the University of Washington Press. She is the winner of the 2021 National Outdoor Book Award, and 2021 Washington State Book Award for non-fiction.